This week, our retailer Downtown Wine and Spirits hooked us up with an amazing beer that reflects the spirit of exchange and collaboration so revered by our entrepreneurial community. The beer is called Stingo Collaboration No. 3, and it is brewed by Cambridge’s own Pretty Things in close collaboration with Boulevard Brewing Co. of Kansas City, MO.

The two are an odd match: Pretty Things employs four people and tenant brews on a 50-barrel system, while Boulevard is one of the largest craft beermakers in the US, boasting a state-of-the-art 150-barrel brewery, and employing over one hundred people. The brewers met at the American Craft Beer Fest in June 2011. During the Belgian Beer Festival in Fall 2011, Boulevard brewmaster Steven Pauwels suggested a collaboration between the breweries as they imbibed at Lord Hobo in Cambridge. Pretty Things’ Martha Holley-Paquette, a native of Yorkshire, offered the idea of the historical sour English ale (or is it the original Flanders Red?). The collaboration would push the envelope for both breweries: Pretty Things had never done a collaboration beer before, and Pauwels, a native Belgian, had not brewed an English-style beer, or considered English ingredients, since arriving at Boulevard over 10 years ago.

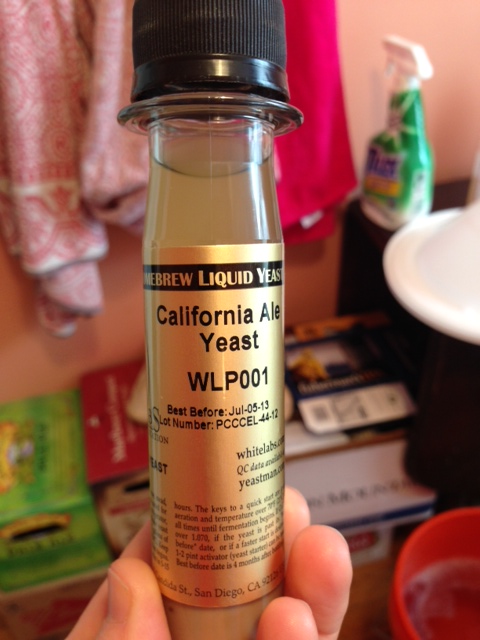

Together, over a series of emails, Pretty Things and Boulevard developed a recipe that combined English beer ingredients and brewing history with current Belgian beer brewing styles. The recipe called for 100% Yorkshire malts, a Yorkshire ale yeast, and a few different English hop varieties. Pauwels remarked that his brewery once threw out some of these hops due their extremely odd aroma.

In April 2012, the Pretty Things brewers traveled to Kansas City to brew Stingo: “We milled in, blended the preliminary batches, tweaked the ageing and ingredients, and most importantly ate more barbecue than any four people should ever eat.” Since Boulevard at the time did not work with foeders – very large wooden tuns used in Belgian brewing – the team created the beer’s “sting” with bacterial fermentation in the brewhouse, adding dry ice to the brew kettle to lower the temperature, thus encouraging bacteria to flourish, producing the “souring” lactic acid. Over the next few months, the brewers experimented from afar with different blends of Stingo batches to arrive at the final product.

Stingo tastes like a dry, brown ale, with a subtle sour “sting” upon sipping, followed by a dry and balanced finish. Pauwels describes Boulevard’s Collaboration No. 3 as “bold and full-bodied, with a big malty nose, hints of dark malt, chocolate, licorice, and black fruits, and just the right amount of tartness in the finish. It pairs exceptionally well with wild game, smoked meats, strong cheeses, and heavily seasoned dishes.”

Allow these brewers to entice you to venture beyond your own venture, and visit the Café this Thursday for a taste of collaboration.