“Don’t Stop the Party” by Pitbull on speed brought to you by Savannah Schilling.

Author Archives: kegomatic

West Coast-East Coast IPA Throwdown: Pliny the Elder vs. Heady Topper

By Robin Coxe

After a nearly two year hiatus, Kegomatic is back! Amy and I have by no means stopped drinking beer, but life got the better of us for a while. Our stints as volunteer bartenders at Venture Café reached their logical conclusion in early 2015. In September 2015, I succumbed to the Sirens’ song of Silicon Valley and decamped from Boston to San Francisco to take on the role of Pointy-Haired Boss of the R&D team at Ettus Research, a National Instruments Company in Santa Clara, CA.

During the interview process, my new employer latched on to the mention of this blog on my resumé and enticed me with a description of Friday afternoon Ettus Research Beer; the tale of this longstanding tradition shall be the subject of a future post. I soon discovered that beer aficionados abound at National Instruments and broke the ice with many new colleagues in Santa Rosa and at NI’s corporate headquarters in Austin with spirited discussions about our favorite brews. After 16 months of buildup, this beer banter came to a head (bad pun intended) last Wednesday 18 January 2017 in Conference Room C at NI Santa Rosa.

During the interview process, my new employer latched on to the mention of this blog on my resumé and enticed me with a description of Friday afternoon Ettus Research Beer; the tale of this longstanding tradition shall be the subject of a future post. I soon discovered that beer aficionados abound at National Instruments and broke the ice with many new colleagues in Santa Rosa and at NI’s corporate headquarters in Austin with spirited discussions about our favorite brews. After 16 months of buildup, this beer banter came to a head (bad pun intended) last Wednesday 18 January 2017 in Conference Room C at NI Santa Rosa.

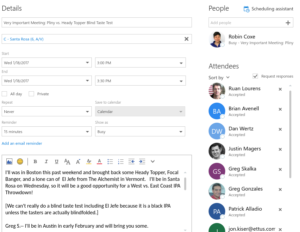

I dutifully sent out an Outlook calendar invite several days in advance entitled Very Important Meeting: Pliny vs. Heady Topper Blind Taste Test. Needless to say, all recipients RSVPed in the affirmative almost immediately. [I should note for the record that I did have several legitimately work-related reasons to visit NI Santa Rosa that day. Trust me.]

Although I am not typically a lover of IPAs– I often compare the experience of drinking most of them to consuming Pine-Sol— I had been talking up The Alchemist’s signature brew, Heady Topper, an 8% ABV double IPA brewed in Stowe, VT, for quite some time. I eventually took the exhortations of my high school English teachers to “show, don’t tell” to heart. Because The Alchemist does not distribute outside of Vermont, these deprived Californians had never experienced it.

Even though Santa Rosa, the county seat of Sonoma County, is squarely in wine country, it also happens to be the home of Russian River Brewing Company, widely considered to be one of the finest breweries in Northern California. As it happens, Russian River also brews an 8% ABV double IPA with legendary status, Pliny the Elder, named after the Roman naturalist (23-79 AD) who discovered hops and perished in the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. As a recent transplant to the Bay Area, I had never had the opportunity to sample it, setting the stage for a head-to-head battle of epic proportions.

During my one previous visit to the Russian River brewpub to fête the release of a product aptly code-named Evil Twin, I focused my beer consumption on the world-class sour ales, Supplication and Consecration. Allegedly, upon tasting one of these polarizing concoctions, one of the more unsubtle VPs visiting from Austin bellowed “this beer tastes like vomit!” within earshot of the entire establishment. But I digress…

Heady Topper and Pliny the Elder have achieved cult followings in the craft beer community on their respective coasts, due in a large part to scarcity marketing. The popular press has written strikingly similar articles about the great lengths that consumers obsessed with Pliny (Exhibit A) and Heady Topper (Exhibit B) go to acquire their limited allotments. Anecdotal observation has revealed that a vast majority of the people who schlep to Stowe or Santa Rosa and stand in line for hours to buy these beers are white men in the 30-44 age demographic. Craft beer makers take note: the Brewers Association has identified women and Hispanics as the principal growth markets for craft beer in America (and, not surprisingly, millennials).

Dan Wertz made good on the promise he had made the week prior while visiting my office and acquired the requisite Pliny the Elder from Russian River. The difficulty of procuring Heady Topper from Vermont presented a more daunting logistical challenge. I had a fortuitously scheduled a 48 hour visit to Boston the weekend before to visit family and friends, and I know People. More specifically, Amy knows a Person, Mike Yeh, who not only owns a condo in Stowe down the street from The Alchemist, but also loves beer. [Mike and I randomly met up for a few drinks at the now-defunct, but allegedly re-opening Mikkeller Bar in Stockholm in the winter of 2014 when we both happened to be in Sweden on business. Happily, there is also a Mikkeller outpost in San Francisco. Yes, it’s in a dodgy neighborhood, but that has hardly prevented me from spending some quality time there.] I was the lucky beneficiary of Mike and Amy’s inscrutably complicated beer trading scheme, ending up with six cans of Heady Topper, eight cans of Focal Banger, one of El Jefe, and a Double Down Gose IPA from Fort Collins, CO. I’m saving that last one for the next time I order pad thai for delivery from my iPhone in SoMa instead of actually cooking.

The United Airlines website confirmed that passengers could transport unlimited quantities of alcoholic beverages in checked luggage on domestic flights. I forked over $25 to The Worst Airline in America and hoped for the best. My down parka and various articles of clothing served as padding for the precious cargo. Zipping the bag shut proved somewhat difficult, but persistence paid off. The transcontinental journey went off without a hitch for both human and beer.

In preparation for the tasting event, I assigned a homework assignment, Amy’s Kegomatic post from April 2015, IPA: Which is the Best Coast? East Coast IPAs tend to have a stronger malt presence and make more use of European hops with spicier flavor profiles than their West Coast cousins, bombs of hoppiness cultivated in the Pacific Northwest. Another older post of Amy’s full of IPA factoids also helps to set the stage.

Photo Credit: Justin Magers

Photo Credit: Justin Magers

At the appointed time, the two contestants prepared for battle and the eager tasters convened. Justin Magers donned his Pliny the Elder t-shirt especially for the occasion. Trang Nguyen, although not a beer drinker, found herself caught up in the significance of the moment and prepared to tabulate the results on the whiteboard. Given that we had ten participants and only four cans of Heady Topper, we had to ignore the exhortation on the can to drink directly from it and had no choice but to ration out the beer in plastic cups. Unfortunately, the office refrigerator was not up to the task of cooling the cans to the perfectly chilled temperature of the bottles of Pliny, handicapping the East Coast entrant from the get-go. And the taste test did not end up being blind. I lacked the time or opportunity to set it up properly, but never mind.

This crowd of beer connoisseurs took their responsibilities seriously and displayed their sophistication and discerning taste by evaluating the two samples properly. A random guy on the Internet named Otto describes the process pretty decently: 1. See, 2. Swirl, 3. Smell, 4. Sip. Ruan Lourens declared that Pliny “probably has the best nose of any beer out there,” an assessment that is difficult to dispute.

Then the double fisting started…

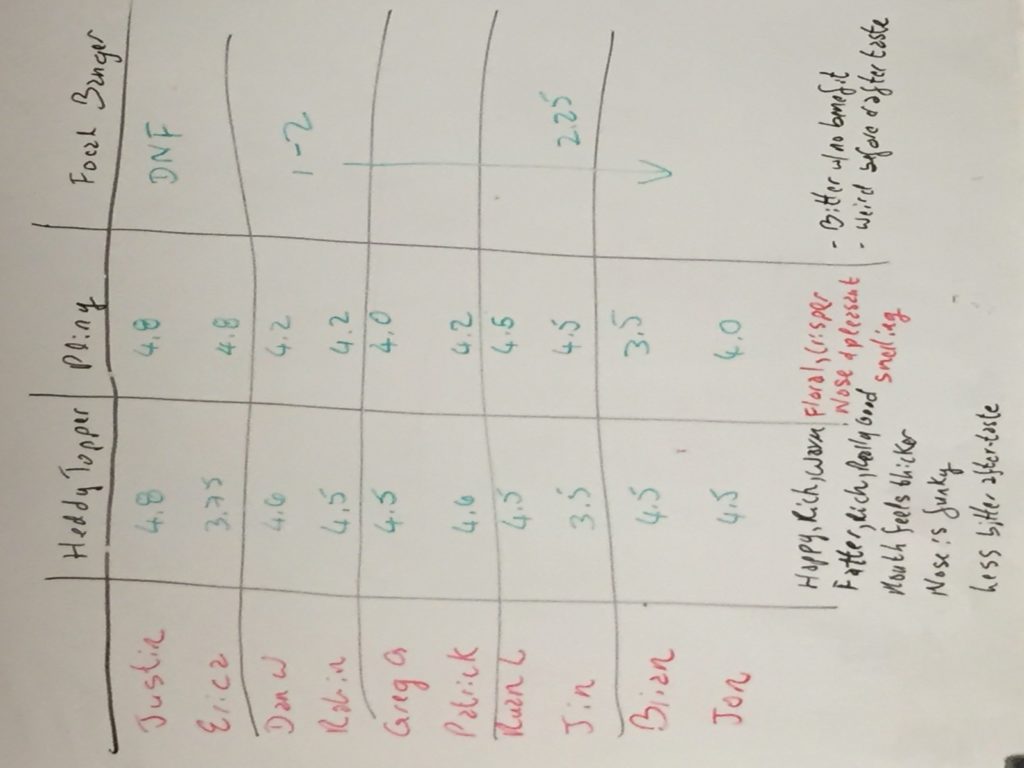

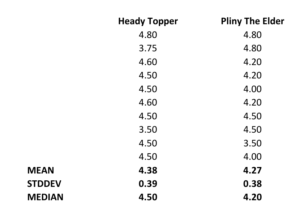

The beers were rated on a scale from 1-5. One is undrinkable. Five is the best beer in the universe. Behold the raw data:

Even an avowed non-hophead like myself could not deny the almost transcendent quality of both of these beers, warranting ratings ≥ 4.0. These two specimens represent craft brewing of the highest order. If I were rewriting the rules, I would insist that each individual must select a winner. Go out on a limb and express a definitive opinion, I say!

Now for the results. Drumroll please…

Heady Topper [4.38 ± 0.39] edged out Pliny the Elder [4.27± 0.38] , but not by a statistically significant margin.

We made the tactical error of tasting The Alchemist Focal Banger last. Although this beer garners a perfect score from Beer Advocate, all of us unanimously agreed that it was disgusting. I offered to ship it back across America to Amy, who professes to like it and expressed dismay that we had spurned it. Instead, she found a happy home for the remaining six cans with her friend Dan who lives in Noe Valley. I am holding the lone can of El Jefe black IPA hostage in my cubicle and intend to use it as bait to lure the Santa Rosa team south to Santa Clara.

Although the label on the can carrier chides drinkers not to be d-bags and to recycle, my sources report that Justin and Dan kept Heady Topper cans as souvenirs.

Although the label on the can carrier chides drinkers not to be d-bags and to recycle, my sources report that Justin and Dan kept Heady Topper cans as souvenirs.

Inevitably, the conversation turned to the impending arrival of Pliny the Younger, named after the Elder’s nephew and adopted son who lived from 61-c.113 AD and Russian River’s seasonal triple IPA [ABV 10.25%]. Pliny the Younger will only be available from 6-17 February 2017. We agreed that in spite of a significant fraction of us being summoned to Austin for management meetings during that time period, we will do our utmost to ensure that sufficient quantities of Pliny the Younger will be acquired and savored.

In the end, Heady Topper successfully infiltrated enemy territory. Although the upstart from Vermont did not emerge with an incontrovertible victory, it proved itself to be an extremely worthy opponent. Mission accomplished!

Beer and Elections

On 4 November 2014, a.k.a. Midterm Election Day, I (Robin) made the grave error of driving to and from work. Stuck in a hellacious traffic jam on the way home, a snippet from the NPR evening economics program Marketplace by Kai Ryssdal caught my attention: We spend more on beer than elections. This story was inspired by post on the Wall Street Journal Washington Wire blog entitled Americans Spend 16 Times as Much on Beer as on 2014 Midterms.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates the Americans shelled out $59.9B on beer in 2013. The Brewers Association has a more optimistic view of the total addressable beer market in the United States, declaring it to be $100B in 2013. [Correction: this figure includes exports.] Craft beer accounted for 14.3% of sales and 7.8% market share (15M bbls of a total 196M bbls). A beer barrel (bbl) equals 31 gallons.

Clearly intended to put the influence of money in politics in perspective, the beer vs. election spending trope compares apples to oranges, so to speak. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, during the 2014 midterm election cycle, $1.64B was spent on behalf of Democratic candidates and $1.75B was spent on behalf of Republicans ($300M of which can be attributed to the Koch Brothers, who, by means of their oil refinery fortune, founded Americans for Prosperity, Official Bank of the Tea Party).

Consider a more relevant beer factoid, annual spending on beer marketing, which happened to total $1.3B in 2012. In fact, the beer industry spent only half as much plying its products upon beleaguered American voters as those PAC people. Most of that election money went towards…well…marketing one candidate or another, often by means of such below-the-belt tactics as robo-calling peoples’ cell phones at dinnertime and bombarding the airwaves with ads that give new meaning to lying with statistics and taking random quotations woefully out of context.

Correlation does not imply causation, of course. I must confess that this infographic about what kind of beer you drink allegedly says about your political inclinations gave me a chuckle. (It was clearly made before Yuengling returned to Massachusetts.) Let’s face it, comparisons between spending on beer and elections are kind of ridiculous. That being said, exercising one’s democratic right to vote in the United States of America frequently involves holding one’s nose while doing so, selecting the lesser of two evils, and then going home and drinking lots of beer, perhaps in the course of playing an Election Drinking Game.

Berliner Weisse: The New Champagne of North America?

By Amy Tindell

I remember my first legal purchase of alcohol fondly: I was only 20 years old, but had embarked on that Dartmouth College right of passage called the “FSP,” or foreign study program. At long last I sat on a high bar stool in a Berlin bar, eagerly taking in the long menu of beers I didn’t know, and made my selection based on name alone: the Berliner Weisse. As long as I studied in Berlin, I would do as Berliners do.

Clearly, I didn’t know what I was getting into. The bartender smiled kindly at my accented order, and inquired, “Mit schuss?” After I responded with a “Wie bitte?” – a polite form of “huh?” – the bartender explained, slowly and (not yet giving up on me) in German, that many people preferred to add “schuss,” a sweet syrup, to balance the taste of the very sour Weisse. I chose the himbeere (red raspberry) over the palmeister (herbal green) flavor. Given the unsophisticated state of my palate at the time, schuss was probably a good choice.

That day was almost exactly 16 years ago, and over those years I’d heard barely a peep from the Berline Weisse… until this summer. Suddenly American craft breweries, including Dogfish Head, New Belgium, Firestone Walker, and The Tap Brewing Company have picked up on the style and interpreted it for the modern market. Today the Berliner Weisse is a sour, fruity, effervescent, low-alcohol wheat beer. The sour taste results from fermentation with a mixed culture of top-fermenting yeast and Lactobacillus bacteria, a microorganism that produces lactic acid and carbon dioxide as it digests the wort. Lactobacillus is commonly used in food processing; it obligingly ferments our cabbage to create sauerkraut and sours our milk to produce creamy yogurt.

These modern American breweries are borrowing from old European traditions. While the precise origins of Berliner Weisse are unknown, two stories emerge as the most popular. The first gives credit to the Huguenots, 17th century religious refugees who migrated to the Berlin area from France and Switzerland. The Huguenots would have picked up Weisse brewing techniques involving Lactobacillus and wheat malt as they passed through Flanders, home of the witbeer and lambic styles. Another theory goes back to the 1520s, with brewer Cord Broihan’s modification of a popular Hamburg beer, which he called Halberstädter Broihan. The style was perfected by Berlin brewers and became fashionable in the 1640s. Whatever its origins, by the early 1800s, the beer was sufficiently popular that Napoleon’s troops famously dubbed it as “the Champagne of the north” during their occupation of Berlin.

That first trip to a Berlin bar piqued my curiosity as to how such a beer was first made and commercialized. Some stretching of my German language skills at a local library revealed that historically, a Berliner Weisse wort was not boiled, allowing Lactobacillus already present on the grain to make its way into the primary fermentation with Brettanomyces ale yeast. As brewers perfected the technique, they learned that the yeast and lactic acid bacteria could be pitched together, and the higher the temperature range, e.g. 63–68° F as opposed to 57–64° F, the more sour the beer would become. Brewers further developed the process after that main fermentation to include kräusening the beer before bottling. This carbonation process, applied most often to lager beers but also to traditional wheat beers, adds freshly fermenting beer to bottle-ready beer, preventing yeast from becoming dormant during the second fermentation and maturation in the bottle, which can take up to two years.

A more contemporary and predictable process starts at low gravity and splits the wort in half for the first fermentation: half is inoculated with ale yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) and the other half with Lactobacillus. After about four weeks, the wort is blended, filtered, stored at 41–50° F for about 13 months. The beer is bottled with a fresh addition of kräusen that includes only the yeast (no Lactobacillus). This modern technique is frowned upon by traditionalists and tends to produce less sour beers.

Part of the reason that Berliner Weisse, along with other sour beers, have been slow to trend is that maintaining Lactobacillus in a brewery is risky, because of the high probably that it could spoil other beers through cross-contamination. Most breweries require separate, dedicated equipment for these beers.

Another reason for the slow trend is that beer drinkers are still developing their palates, and even the most sophisticated American imbibers have been too busy familiarizing their taste buds with the bitter flavors of hops to entertain the sour notes of these traditional European styles. Nonetheless, the recent boom of craft breweries has resulted in an increased willingness to experiment, both on the part of brewers and consumers. As a somewhat unique American consumer, however, I got my start at this traditional, European end of the brewing spectrum. After 16 years and many diversions in my beer education, I’m ready to return to my German roots.

The Battle of the Growler

By Amy Tindell

It’s become part of my travel modus operandi to target a local source for information regarding the area beerscape at my destination. Upon a recent trip to Atlanta, my cousin Brad did not disappoint, pointing me to a unique and controversial feature of Georgia’s beerscape: the Beer Growler retail store. For those unfamiliar with the term, a growler is a jug, usually glass but sometimes ceramic, that is used to transport beer. The 64 ounce growler is the most popular size, though others are available, and the glass is usually amber in color, which helps to avoid skunking the beer.

Prior to my trip to Atlanta, I hadn’t realized that these beer vessels produced so much controversy. There’s debate even over the origination of the name “growler,” though most accounts go back to the steel pail that people used to transport beer to their homes in the ‘20s and ‘30s. One story describes a “burping” sound made by filling the pail with beer, which people believed sounded like a growl. Another version recites that the name reflects the hissing sound of gas escaping the pail’s lid as it was opened.

Curious as to this novelty that does not exist in Massachusetts, I pulled my rental car into The Beer Growler’s parking lot. Admiring the Digital Pour screen looming over 45 taps, I asked the staff how long they had been in business. They explained that while the growler has been around for some time, its legality for sales in Georgia traditionally fell in a grey area: the law did not prohibit the sale of growlers by stores for off-premises consumption, but it was not expressly authorized either, and it was further unclear whether a growler would be considered an “original package” appropriate for the sale of beer under Georgia law.

The staff expounded on their company’s history detailing how the Beer Growler’s attorney sent a letter to the Georgia Department of Revenue requesting a reinterpretation of packaging law that would allow the growler’s plastic, heat-gunned seal to qualify it as an “original package.” The Department of Revenue obligingly responded: “pursuant to the Georgia Alcoholic Beverage Code, ‘growlers,’ or similar containers may be appropriately used so long as it is at a licensed retail off premise location that does not deal in distilled spirits by the package.” The letter then clarified that local ordinances maintained the right to a more restrictive interpretation of the law. Thus, only certain Georgia cities that have addressed this issue allow growler retailer stores.

As Brad promised, I would not leave thirsty, as Georgia law also allows for three beer samples to aid in consumer choices at stores like The Beer Growler. I worked with the staff to identify their favorite local brews to taste and watched as they filled growlers with my selections. After my second taste, one particularly zealous employee told me about a brew-off event at Jekyll Brewing just around the corner in Alpharetta, but warned me that I would not be permitted to buy growlers from the brewery.

It turns out that yet another fight regarding growlers has been brewing in Georgia over whether breweries can themselves sell growlers containing the beer that they make. Currently Georgia follows the three tier distribution system, wherein alcohol manufacturers, including breweries, are not allowed to sell their products directly to the public, in growlers or otherwise, but may only make the alcohol to sell to distributors, which then sell the alcohol to retailers (e.g., stores, restaurants, bars). As a solution, the Georgia Craft Brewer’s Guild backs Georgia House Bill 314 and its companion Senate Bill 174, known to supporters as the “fill the growler” bill, to allow a limited exception to the three tier system in which craft breweries may sell up to 288 ounces of beer per person per day for off-premise consumption. While the Georgia Beer Wholesalers Association, representing distributors, warns of the destruction of what it considers an effective three tier system, brewers argue that they have no intention of endangering their relationships with their trusted and essential business partners, and that most of their business would continue to follow traditional distribution practices. Selling such a small amount of product directly to consumers would improve brewers’ cash flow in addition to strengthening their brands and attracting more visitors, which increases profits for everyone.

Walking out of the store with growlers containing my local brews, I wondered why I’d never done that in Massachusetts before. After some research into Massachusetts alcoholic beverage law, I found that the Commonwealth, like Georgia, does not specifically address the growler, creating a grey area for would-be entrepreneurs. The Massachusetts Alcohol Beverage Control Commission’s regulation concerning labels and containers specifies that wholesalers and importers may use only containers furnished by manufacturers, and forbids misleading label statements as well as defacing, removing, or covering any brand on a container. These and other regulations support the custom currently in place wherein Massachusetts brewers, unlike their Georgian peers, may sell their beer to consumers, but only in their own branded growlers. Select retailers also sell branded growlers that may be refilled only by the labeled brewery. One could imagine why Massachusetts would-be entrepreneurs would find it prohibitive to operate a retail store with 45 rotating taps, each requiring its own specific container, with only limited ability for customers to refill their growlers.

Further research revealed a great variety in state practices regarding growlers due to the (perhaps purposeful) lack of comprehensive regulation by the federal TTAB on the subject. For example, other states like Oregon and New York have much more lax laws that permit refilling of growlers, by brewers and retailers, regardless of the branded labeling. Georgia, where distributors and retailers profit from excluding breweries from selling their products directly to consumers for off-premises consumption, provides a clear example of how regulations may benefit some parties over others. However, it also illustrates how some entrepreneurs and one creative attorney can inspire a game-changing reinterpretation of the law by the state.

Whatever structure a state’s law may provide, I definitely learned that showing up with a few growlers, even if it makes you ever-so-slightly late to a pre-wedding lunch, puts a smile on people’s faces, and allows them to (humor you while they) try something new. Indeed, the most recent update I received from Georgia involved Brad returning to The Growler Store to refill those very same growlers with new brews. An entrepreneur himself, I can only hope that Brad was inspired to create his own law-bending game-changer.

Great Divide: I Believe

By Amy Tindell

My parents and I were looking for a lunch spot, but we found ourselves at Great Divide Brewing Company instead. To be fair, we’d heard rumors of collaborations with food trucks, but the Denver neighborhood home of the award winning brewery had no extra space with the bustle of the day’s Rockies game at Coors Field.

The most noticeable thing about Great Divide is its outdoor fermentation tank farm. Next to the building that houses the brewery and tap room on Arapahoe Street stand neat rows of 300 barrel insulated fermentation tanks which give Great Divide a maximum capacity of 65,000 to 70,000 barrels per year. Great Divide’s founder Brian Dunn started small in 2001 when he bought the building, an old dairy processing plant, but strategically added fermentation tanks over the years to increase the brewery’s capacity as its popularity grew. The space is now full.

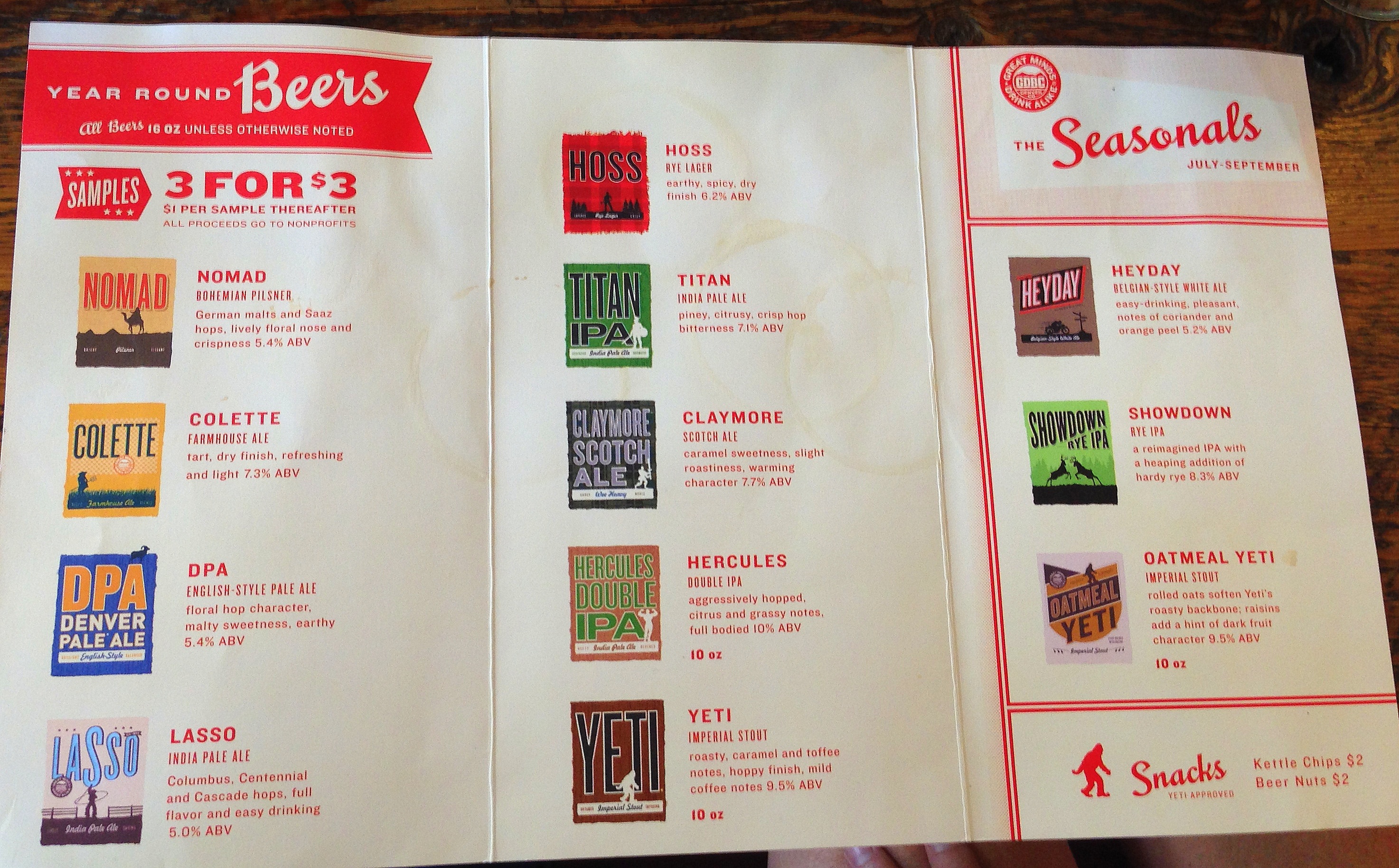

Inside, the brewing equipment shines through large windows in the tap room. Great Divide strives to maintain sustainable brewing practices, including using mainly locally grown and malted grains, reusing grey water, and recycling all cardboard and glass. Tap room patrons are encouraged to bring their own food, from food trucks or nearby establishments, to pair with the 16 year round and seasonal beers on tap. Around the tap room hang different versions of logo art featuring Yeti, the face of Great Divide’s imperial stout, with the caption: “I believe.” My parents and I, foodless but believing, ordered a strategic set of samples, the proceeds of which go to nonprofits.

Inspired by the artwork for Great Divide’s Colette, I took a risk on Dunn’s homage to the centuries-old beverage of choice of Belgian farm workers. Made with barley, wheat and rice, and fermented with no fewer than four different yeast strains, Colette is tart and fruity, with notes of lemon and pear, with a dry finish that makes it refreshingly light. The funky yeasty taste that is the signature of the Belgian style is not overpowering, making Colette a well-balanced beer.

My mom’s favorite sample was Claymore, named for the Scottish two-handed longsword used in medieval times and made famous by William Wallace. She noted the roasty caramel malt character of Claymore, characteristic of the wee-heavy beers of Scotland. The beer poured deep ruby in color, and due to its modest hop profile and 7.7% ABV, tasted sweet and went down warm. As the website states, “this beer only requires one hand, but it’ll still make you feel like nobility.”

My dad decided that he believed, strongly, in Yeti. Yeti is Great Divide’s imperial stout with 9.5% ABV, pouring dark and heavy into the glass. Dad said it smelled like a cup of coffee, but when sipped, the roasty notes gave way to an unexpected malty sweetness, though the finish was bitter. Like the Claymore, the booziness of the beer created a pleasant warming effect.

Our sampling complete, we ventured off in search of food. Although our visit was relatively short, we planned to return to Great Divide in the near future, in its new spot on Brighton Boulevard in Denver. The Arapaho Street location will transition to a small-batch production facility, while the new digs will feature an 80,000 barrel capacity brewery, a larger tap room, and a beer garden. With change and expansion afoot, Great Divide’s fans have a lot more to believe in than Yeti.

A British Beer Odyssey

By Robin Coxe

In which Robin, at long last, returns from beer blogging hibernation…

My engineering design team, with members based in Ireland, England, Spain, Poland, and the US, spends an inordinate amount of time huddled around Polycom Batphones at our various work sites on conference calls. Fortunately, our corporate overlords appreciate the benefits of periodic face-to-face collaboration, which tends to result in weeklong bursts of exceptional productivity about once per quarter, fueled in part by the beers of the region we happen to be visiting. I spent the first week of June at the company office in Bath, a city of 90,000 residents situated in Somerset in the southwest of England, approximately 100 miles west of London.

Our local hosts had a quintessentially British beer-themed adventure in store for us after our first full day at the office, Tuesday 3 June 2014. Shortly after lunch, once Queenie the tea cosy had been refilled with a fresh pot, Mark began poring over the early evening train schedule from Bath Spa to Freshford, returning about 4 hours later from Bradford-on-Avon. After the most economical type of tickets had been settled upon (First Great Western offers substantial group discounts, as it happens), we were instructed to convene at 18:30 in front the railroad station and to wear sensible shoes.

At the appointed time, we crammed into the train along with droves of commuters for the epic 9 minute journey to Freshford. After disembarking, we ascended Station Road, turned left, and headed down The Hill to our first destination, The Inn at Freshford, a 16th century building with original timber beams on the banks of the River Frome. Our group saw no signs of the sinkhole that was “big enough to swallow a double decker bus” that had mysteriously appeared next to the place in early April.

The Casque Marque seal mounted to the left of the doorway caught my attention. I later learned through the magic of the Internet that this organization accredits pubs in the UK and Ireland serving cask ale, also referred to as real ale, what Americans tend to associate with stereotypically warm (50-55 degrees F) British beer. The accreditation process involves unannounced quality inspections in which the temperature, taste, aroma, and appearance of the ale is assessed. Of course, there is a smartphone app called “Cask Finder” that enables the discerning cask ale drinker to identify the nearest Casque Marque certified pub. Cask beer has been enjoying a resurgence in recent years, accounting for about 15% of beer sales in the UK. Woman are the fastest growing segment of cask ale drinkers, a largely untapped (pun intended) market of discerning beer consumers, if I do say so myself.

Upon entering The Inn, we were immediately greeted by the resident pub dog, a large, friendly beast. Health regulations in most states prohibit non-service animals inside any establishment serving food, so a dog in a bar is a rare sight indeed in the US. All of the taps featured beers from Box Steam Brewery.

Founded in 2004 in the nearby village of Holt, Box Steam brews their beers by hand in steam-heated copper vessels using floor-malted Maris Otter barley from Warminster Maltings, the oldest supplier of malt in the Britain. Built in 1855, operated by Guinness from 1950-1994, and privately owned since, Warminster Maltings caters to the increasing number of British microbrewers such as Box Steam who take advantage of the Progressive Beer Duty adopted in the UK in 2002, whereby smaller breweries pay less tax on their wares than larger producers. This tax incentive differs from the flat discount on each barrel enjoyed by microbreweries in the USA.

Box Steam’s first brewery was located near the Box Tunnel, a railway tunnel that bores through the eponyomous hill between Bath and Chippenham designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the chief engineer of the Great Western Railway. The completion of the Box Tunnel in 1841 capped off the final link in the rail line connecting London with the southwest of England and Wales. The brewers at Box Steam have drawn inspiration from the legacy of Brunel and have embraced the train theme wholeheartedly.

For the first pint of the evening, I opted for the Tunnel Vision amber bitter, an easy drinking, cask-conditioned 4.2% ABV amber ale with traces of caramel and a slight hint of hops at the finish. English Bitter, unlike the West Coast hop-bomb IPAs, which, for whatever reason, are taking America by storm, does not taste particularly bitter. Nor should an English Bitter Ale be confused with bitters, the aromatic, botanical alcoholic concoction consumed after gluttonous meals as a digestif or used for flavoring cocktails.

After quaffing down our beverages in the outdoor beer garden, newly reconstructed over the aforementioned sinkhole, we set out on foot, over the river, through the woods, past some sheep, and alongside the Kennet and Avon Canal towards our next destination. This leg of our route covered the northern half of the so called Two Valleys Walk, documented in impressive detail here.

After a lovely 20 minute stroll through the Wiltshire countryside, we arrived in the hamlet of Avoncliff, the next stop along the Great Western Railway line. We traversed and subsequently walked underneath a bridge at the point where the canal, routed through an aqueduct, crosses the River Avon. We approached our second stop, the Cross Guns Free House, another almost ridiculously scenic 16th century relic complete with terraced garden and a vintage ice cream truck parked out front. Walking a mile seemed to accelerate the rate at which Pint #1 percolated from mouth to bladder, so before placing my order, I made a beeline for the loo located in an outbuilding.

Cross Guns also featured the brews of Box Steam on draught. The hopheads in our midst opted for the Derail Ale, an IPA that pays homage to Brunel’s flawed early steam locomotive designs unaptly named “Thunderer” and “Hurricane.” Another hoppy concoction, the Piston Broke golden ale, immortalizes another of Brunel’s engineering missteps, the “atmospheric” railway design for the South Devon Railway that relied on forced air pressure from a series of stationary air pumps to propel trains on the GWR extension between Exeter and Plymouth. Pistons attached to the trains ran through a continuous vacuum pipe laid down the center of the tracks.

The system required leather flaps to form vacuum seals in the pistons that failed repeatedly. The vacuum sucked out the natural oils from the leather, making it vulnerable to water and cold. Tallow applied to re-lubricate the leather proved irresistable to rodents. The atmospheric railway was shut down in 1848 after operating for less than a year, at which point the South Devon Railway converted back to conventional steam locomotives. Although “Brunel’s atmospheric caper” did not end well, the technology has withstood the test of time—an atmospheric airport train opened in Brazil just last year in advance of the World Cup.

The “Free House” in the name would suggest that the Cross Guns would not be encumbered by the so-called UK “beer tie”, an arrangement whereby a pub is obligated to buy its beer from a particular brewery or pub conglomerate. However, the Box Steam Brewery lists both The Inn at Freshford and The Cross Guns at Avoncliff in the “Our Pubs” section of their website, so the exact financial relationship between the brewery and the two pubs is unclear. The beer tie manifests itself in several different forms. In some instances, the brewery owns the pub outright and either rents it out to an operator/manager via a tenancy agreement or directly employs the publican. In an alternative arrangement, a brewery may extend a mortgage to the pub owner with an exclusivity clause. The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) has led lobbying efforts in recent years to reform and regulate the beer tie, citing price gouging and other anti-competitive practices.

Beer tie arrangements are not allowed in the US, as regulatory agencies have frowned upon vertical integration in the alcoholic beverage industry since the conclusion of Prohibition in 1933. Instead, all US states except Washington have instituted a variant of the three-tier distribution system (producers, distributors, and retailers), a subject of intense debate in American craft beer circles. [Coming soon on Kegomatic.com: a discussion of proposed modifications to regulations governing the three-tier system in Massachusetts.]

Anyway, back to the Box Steam beer itself… Intent on sampling as much English Bitter as possible, I chose the more optimistically named Chuffin’ Ale, a 4.0% ABV brown best bitter that made its debut in 2010 on the 175th Anniversary of the Great Western Railway. The Chuffin’ Ale, brewed with English Fuggles hops and Maris Otter and Crystal malts with added wheat, has been described by beer snobs as having “hints of crème brûlée,” a characterization that I did not dispute as I leisurely sipped it down on at a picnic table by the river.

Our dinner reservation awaited, so we eventually brought ourselves to press onward towards Bradford-on-Avon. It did not escape my notice that as we strolled along the canal for the final mile of our journey, the guys nipped off one by one into the woods to relieve themselves.

By the time we arrived at our destination, I was cursing the anatomical disadvantages of being female. Fortunately, the Three Gables in Bradford-on-Avon had spotlessly clean toilets. I must confess to having no recollection whatsoever of what I ate (scallops were perhaps involved), although I do remember thinking that the establishment went a long way towards resurrecting the unfortunate reputation of British cuisine and customer service. This most memorable evening was punctuated by the return train that conveyed us back to Bath arriving exactly on schedule.

At Greenbush, with just enough time for a little Retribution

By Amy Tindell

It had been a long, hard day of self-sacrifice, forcing myself to consume our bounty of specialty cheeses, cherries, strawberries, blueberries, carrots, olives, almond croissants, and cookies from the local farmer’s market, on a sunlit beach no less, and then jaunting through those shady Michigan woodlands that smelled of springtime. Those arduous chores now complete, and with the afternoon clouds rolling in, we reluctantly relegated ourselves to the nearby brewery to drown our sorrows. Pulling into the town of Sawyer, our caravan was greeted by the old-style letters atop the roof of the building spelling simply “BREWERY.”

The sky not-so-subtly suggested that the storm was rather imminent, but we delighted the hostess at Greenbush Brewing Company by locating some unused space on the outdoor patio and agreeing to occupy it. The patio sits along some old railroad tracks, and a quick internet search revealed the brewery’s connection to them: “in 1951 a freight train derailed at the Flynn road crossing, rode the rails for a mile and plowed into the building. We hope our beer can make that sort of impact on you.” With that in mind, we chose our tasting flights with care.

My favorites were Anger, Retribution, and Doomslayer. Anger is a black IPA made with Columbus, Amarillo, Simcoe, and Cascade hops, and Belgian dark malts, weighing in at 7.6% ABV. True to its name, the unique mix of grapefruity citrus flavors mixed with more roasty toffee notes would be sure to distract from a day of pent up emotion. I mused that the brew walks a line close to a porter. As thunder sounded in the distance, we observed that Retribution poured a deep dark brown color, and smelled nutty, earthy, and floral. There was some nuttiness to the taste, but cocoa and coffee flavors dominated, with sweetness up front. In addition to the Belgian grain bill and two varieties of hops, the recipe includes brown sugar, golden raisins, dark raisins, and honey.

We moved on to the last taste as the darkness of the sky grew more ominous. Doomslayer, made with maple sap, was perhaps the most interesting brew, pouring black into the glass, smelling and tasting of chocolate, maple, and some spice. The sweetness from the sap along with the 8.9% ABV nicely rounded out Doomslayer – and our tasting session – as the patio cleared to make way for the storm.

On the way out, I noted the brewing system that produced those beers through the picture window in the taproom. The owners, Scott Sullivan and Justin Heckathorn, home-brewed for years before moving to their current copper 7 barrel brew kettle that was once housed in a men’s only establishment in an old Italian neighborhood in San Francisco, complete with a “self-flushing spittoon” under the bar (i.e., a urinal). While Greenbush takes pride in the “long and sordid history only befitting our line of beers,” they take care to note that they were not able to procure the self-flushing spittoon along with the brewing system. However, they do offer 12 beers on tap on a daily basis, for immediate consumption or by the growler, along with a tempting food menu.

Fortified by the beer, we were not perturbed by the minor soaking from the storm on our way back to the caravan. It was only once we were belted safely into our cars, on our way to dinner at Café Gulistan, that the sky unleashed its very own Anger.

Brewers Association: We Define the “Craft Brewer,” But Not What It Makes

By Amy Tindell

While there is no “official” definition of “craft beer,” the Brewers Association of Boulder, CO defines a “craft brewer” to determine eligibility for certain marketing and lobbying support within its membership. The challenge in creating such a definition, however, is that “craft” means different things to different people and to different businesses.

The non-profit trade group has roots in the U.S. going back to the 1940s, and has evolved to include and connect commercial brewers, homebrewers, distributors, suppliers, retailers, and individuals in the beer industry. Since 2005, the Brewers Association has stated that a craft brewer must be 1) small, 2) independent, and 3) traditional. While these terms have stuck, what they mean has been revised many times, most recently this past February 2014, with significant consequences for many brewers. The organization also revised its statement of purpose, mission and goals.

Previous Definition

To promote and protect small and independent American brewers, their craft beers and the community of brewing enthusiasts.

2014 Definition

To promote and protect American craft brewers, their beers and the community of brewing enthusiasts.

The main change to the organization’s stated purpose was the removal of the term “craft beer,” because it is not defined by the Brewers Association, and the shift in focus to American “craft brewers,” which was redefined in the February 2014 meeting.

SMALL

Previous Definition

Annual production of 6 million bbls of beer or less. Beer production is attributed to a brewer according to the rules of alternating proprietorships. Flavored malt beverages are not considered beer for purposes of this definition.

2014 Definition

Annual production of 6 million barrels of beer or less (approximately 3 percent of U.S. annual sales). Beer production is attributed to the rules of alternating proprietorships.

The big news for the term “small” broke in 2010, when the Brewers Association increased the annual production cap from 2 million bbls to 6 million bbls per year. The Association made that change to accommodate one of its oldest members, Boston Brewing Company (a.k.a. Sam Adams), whose capacity was poised to surpass the 2 million bbl cap. Many smaller brewers, however, continue to protest the change because they believe that larger brewers should not be entitled to receive the same marketing, lobbying, and other support offered by the organization only to craft brewers. Accordingly, the parenthetical added this year is meant to put the rather large-sounding 6 million bbl cap into perspective, highlighting the small market share that the figure represents, at least compared to giants of the American beer industry such as MillerCoors and Anheuser-Busch. The other change this year was to remove the flavored malt beverage exclusion from the “small” category and add it to the “traditional” definition (see below), where it more logically belongs.

The statement about alternating proprietorships is not new this year, but remains important to breweries that share facilities. The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau allows a host brewer and any tenants in a single licensed brewing facility to account separately for their own beer production, thus potentially remaining eligible for certain benefits including reduced tax rates accorded to only small production breweries.

INDEPENDENT

Previous Definition

Less than 25 percent of the craft brewery is owned or controlled (or equivalent economic interest) by a beverage alcohol industry member that is not itself a craft brewer.

2014 Definition

Less than 25 percent of the craft brewery is owned or controlled (or equivalent economic interest) by a beverage alcohol industry member that is not itself a craft brewer.

The description of “independent” as it relates to a brewer was not changed this year, but had been revised previously to align more consistently with terminology commonly used in the alcoholic beverage industry. Separately, the Brewers Association explains that craft brewer independence is important because craft brewers are better able to maintain integrity in what they brew when they are free from a “substantial interest by a non-craft brewer.” They highlight this idea, and a call for improved transparency in the brewing industry, in their craft vs. crafty statement.

However, when the ownership requirement was implemented in 2012, it excluded many former “craft brewers” overnight, including Goose Island, Magic Hat, Pyramid, Mendocino, Fordham, Old Dominion, Widmer, Coastal, Kona, and Redhook. For example, Kona, Widmer, and Redhook were no longer considered “craft” because they were part of the Craft Brew Alliance, approximately 1/3 owned by AnheuserBusch-InBev. These breweries stand in contrast to brands like Shock Top and Blue Moon, which were developed, brewed, marketed, and sold by Anheuser-Busch and Miller-Coors, respectively, since inception.

While certain breweries suddenly lost some support offered by the Brewers Association, it is questionable whether a craft beer drinker would feel obligated, under the Association’s rules, to suddenly avoid former craft beers like Kona’s highly rated Wailua Wheat; one commentator has likened it an indie music lover ceasing to buy The Black Keys albums after 2006, when they signed with Nonesuch Records, a subsidiary of Warner Bros. Either way, beer and music enthusiasts alike take interest in the origins of their pastimes, and as consumers, are left to make their own decisions regarding what is “good.”

TRADITIONAL

Previous Definition

A brewer who has either an all malt flagship (the beer which represents the greatest volume among that brewers brands) or has at least 50 percent of its volume in either all malt beers or in beers which use adjuncts to enhance rather than lighten flavor.

2014 Definition

A brewer that has a majority of its total beverage alcohol volume in beers whose flavor derives from traditional or innovative brewing ingredients and their fermentation. Flavored malt beverages (FMBs) are not considered beers.

This year’s revisions to the “traditional” prong of the craft brewer definition attracted the most attention and wrought the most significant consequences for brewers. The previous definition required a craft brewery to either produce an all-malt flagship beer, or to make at least half of its total product from only barley malt, and not other sugar sources like rice or corn. In 2014, however, the Association recognized adjunct brewing as craft brewing, perhaps because many brewers have traditionally brewed with what is locally available to them.

Some members argue that the change could compromise the quality of craft brewing, but others point out that the revised definition also encourages innovation and experimentation. The Brewers Association now maintains, “Craft beer is generally made with traditional ingredients like malted barley; interesting and sometimes non-traditional ingredients are often added for distinctiveness.” It further asserts, “The hallmark of craft beer and craft brewers is innovation… Craft brewers interpret historic styles with unique twists and develop new styles that have no precedent.”

The change to “traditional” now includes under the umbrella of craft brewers mid-size, older breweries including Yuengling, August Schell, and Narragansett, which brew with non-barley malt ingredients because those were the local ingredients available to them when they were founded in the 1800s. For example, Yuengling, America’s oldest brewery (founded in 1829), historically includes corn grits in addition to barley malts in its brew recipe. After 185 years, Yeungling will become an official craft brewer overnight.

As of this year, the Brewers Association takes on as its mission: “By 2020, America’s craft brewers will have more than 20 percent market share and will continue to be recognized as making the best beer in the world.” The Association continues to support “craft brewers” by developing and promoting access to raw materials, supporting research in brewing safety, sustainability, education and technology, providing legislative and regulatory support, educating consumers, and fostering a network of beer enthusiasts. It encourages craft brewers to be active in their communities through philanthropy and volunteerism, and to maintain their distinctive approaches to interactions with consumers. However, the Brewers Association has left to you, the beer enthusiast, the job of defining the elusive “craft beer.”

The Hipster Strategy for Preventing Skunked Beer

By Amy Tindell

You may have noticed the recent trend of craft brewers releasing their wares in cans, and summarily chalked it up to an attempt to appeal to all those Pabst Blue Ribbon-loving hipsters. In some cases, like that of Evil Twin’s Hipster Ale, or Churchkey – the beer not the bar – the trend’s target is quite blatant.

However, canning beer serves a different purpose that is based on science: it prevents beer from getting “skunked.” A beer is skunked, or “light-struck,” when natural light hits isohumolones, the chemical compounds that contribute to the bitter taste of hops in beer. A photochemical reaction causes the isohumolones to break down and combine with sulfur compounds in the beer, to create 3-methylbut-2-ene-1-thiol (3-MBT). The “thiol” at the end of that name reflects the presence of sulfur and serves as a warning of the offensive smell that it produces. 3-MBT is chemically very similar to isopentyl mercaptan, or skunk spray, and so potent that some individuals can detect it at concentrations of one-billionth of a gram in a 12-ounce beer. Thus, it does not take a lot to skunk a beer, and it can occur faster than Phosphorescent can tell you to Ride On in your skinny jeans and fedora hat.

Cans are one solution to preventing skunked beer, because they block light from reaching the beer. Cans have other practical advantages, including that they maintain a more airtight seal than bottles to protect against oxidation. Additionally, cans are more easily stackable, more light-weight, and won’t break on that bike ride home from the corner store. Canned beer even chills faster than bottled beer, so that it’s ready to pair with your kale, ramps and bacon tacos from that food truck down the street in no time.

Regardless of craft beer marketers’ strategy for a target audience, cans are practical and becoming more prevalent by the day. Indeed, the increasing popularity of craft beer cans may just be the kink in attempting to cater to this particular subculture, given the hipster taste for the culturally obscure. However, craft brewers experimenting with canning can still rejoice, because those of us who may be slightly behind the trends also like to take our time to appreciate a good beer, and wouldn’t want it to get skunked as we listen to way-too-mainstream bands like The Knife or Chvrches.