By Amy Tindell

It’s become part of my travel modus operandi to target a local source for information regarding the area beerscape at my destination. Upon a recent trip to Atlanta, my cousin Brad did not disappoint, pointing me to a unique and controversial feature of Georgia’s beerscape: the Beer Growler retail store. For those unfamiliar with the term, a growler is a jug, usually glass but sometimes ceramic, that is used to transport beer. The 64 ounce growler is the most popular size, though others are available, and the glass is usually amber in color, which helps to avoid skunking the beer.

Prior to my trip to Atlanta, I hadn’t realized that these beer vessels produced so much controversy. There’s debate even over the origination of the name “growler,” though most accounts go back to the steel pail that people used to transport beer to their homes in the ‘20s and ‘30s. One story describes a “burping” sound made by filling the pail with beer, which people believed sounded like a growl. Another version recites that the name reflects the hissing sound of gas escaping the pail’s lid as it was opened.

Curious as to this novelty that does not exist in Massachusetts, I pulled my rental car into The Beer Growler’s parking lot. Admiring the Digital Pour screen looming over 45 taps, I asked the staff how long they had been in business. They explained that while the growler has been around for some time, its legality for sales in Georgia traditionally fell in a grey area: the law did not prohibit the sale of growlers by stores for off-premises consumption, but it was not expressly authorized either, and it was further unclear whether a growler would be considered an “original package” appropriate for the sale of beer under Georgia law.

The staff expounded on their company’s history detailing how the Beer Growler’s attorney sent a letter to the Georgia Department of Revenue requesting a reinterpretation of packaging law that would allow the growler’s plastic, heat-gunned seal to qualify it as an “original package.” The Department of Revenue obligingly responded: “pursuant to the Georgia Alcoholic Beverage Code, ‘growlers,’ or similar containers may be appropriately used so long as it is at a licensed retail off premise location that does not deal in distilled spirits by the package.” The letter then clarified that local ordinances maintained the right to a more restrictive interpretation of the law. Thus, only certain Georgia cities that have addressed this issue allow growler retailer stores.

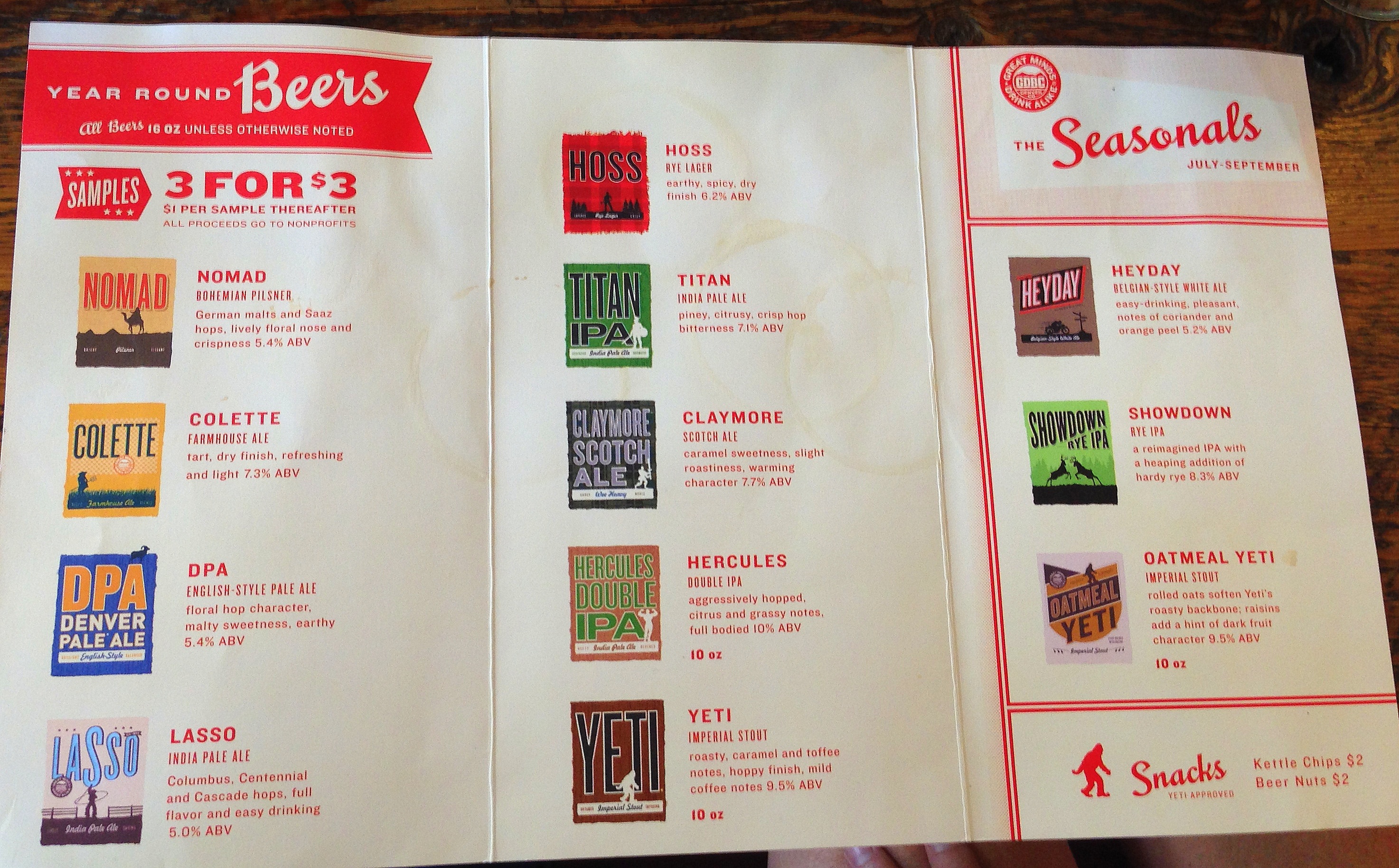

As Brad promised, I would not leave thirsty, as Georgia law also allows for three beer samples to aid in consumer choices at stores like The Beer Growler. I worked with the staff to identify their favorite local brews to taste and watched as they filled growlers with my selections. After my second taste, one particularly zealous employee told me about a brew-off event at Jekyll Brewing just around the corner in Alpharetta, but warned me that I would not be permitted to buy growlers from the brewery.

It turns out that yet another fight regarding growlers has been brewing in Georgia over whether breweries can themselves sell growlers containing the beer that they make. Currently Georgia follows the three tier distribution system, wherein alcohol manufacturers, including breweries, are not allowed to sell their products directly to the public, in growlers or otherwise, but may only make the alcohol to sell to distributors, which then sell the alcohol to retailers (e.g., stores, restaurants, bars). As a solution, the Georgia Craft Brewer’s Guild backs Georgia House Bill 314 and its companion Senate Bill 174, known to supporters as the “fill the growler” bill, to allow a limited exception to the three tier system in which craft breweries may sell up to 288 ounces of beer per person per day for off-premise consumption. While the Georgia Beer Wholesalers Association, representing distributors, warns of the destruction of what it considers an effective three tier system, brewers argue that they have no intention of endangering their relationships with their trusted and essential business partners, and that most of their business would continue to follow traditional distribution practices. Selling such a small amount of product directly to consumers would improve brewers’ cash flow in addition to strengthening their brands and attracting more visitors, which increases profits for everyone.

Walking out of the store with growlers containing my local brews, I wondered why I’d never done that in Massachusetts before. After some research into Massachusetts alcoholic beverage law, I found that the Commonwealth, like Georgia, does not specifically address the growler, creating a grey area for would-be entrepreneurs. The Massachusetts Alcohol Beverage Control Commission’s regulation concerning labels and containers specifies that wholesalers and importers may use only containers furnished by manufacturers, and forbids misleading label statements as well as defacing, removing, or covering any brand on a container. These and other regulations support the custom currently in place wherein Massachusetts brewers, unlike their Georgian peers, may sell their beer to consumers, but only in their own branded growlers. Select retailers also sell branded growlers that may be refilled only by the labeled brewery. One could imagine why Massachusetts would-be entrepreneurs would find it prohibitive to operate a retail store with 45 rotating taps, each requiring its own specific container, with only limited ability for customers to refill their growlers.

Further research revealed a great variety in state practices regarding growlers due to the (perhaps purposeful) lack of comprehensive regulation by the federal TTAB on the subject. For example, other states like Oregon and New York have much more lax laws that permit refilling of growlers, by brewers and retailers, regardless of the branded labeling. Georgia, where distributors and retailers profit from excluding breweries from selling their products directly to consumers for off-premises consumption, provides a clear example of how regulations may benefit some parties over others. However, it also illustrates how some entrepreneurs and one creative attorney can inspire a game-changing reinterpretation of the law by the state.

Whatever structure a state’s law may provide, I definitely learned that showing up with a few growlers, even if it makes you ever-so-slightly late to a pre-wedding lunch, puts a smile on people’s faces, and allows them to (humor you while they) try something new. Indeed, the most recent update I received from Georgia involved Brad returning to The Growler Store to refill those very same growlers with new brews. An entrepreneur himself, I can only hope that Brad was inspired to create his own law-bending game-changer.